The Construction of Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B

A very personal and technical written and photographic history, by James MacLaren.

Page 6: The Technical Story Begins in Earnest - Early Morning, and Things Are Now Happening.

| Pad B Stories - Table of Contents |

I've been here for a little over six months, now.

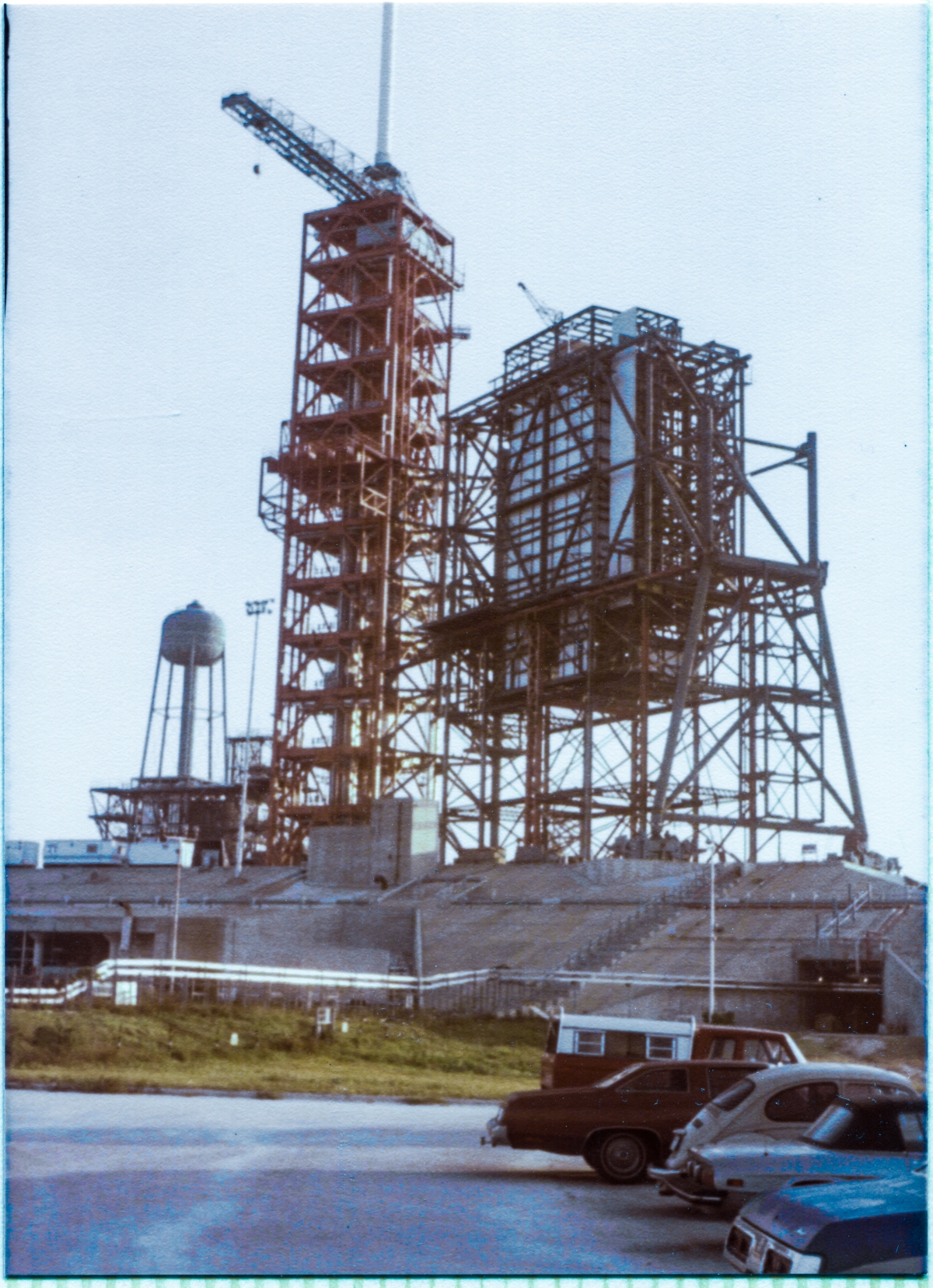

This photograph was taken perhaps four months after the previous pair, standing in the same place in front of the Sheffield Steel field trailer at Pad B, looking at the same thing, and the changes are profound and manifold.

And by now, my job as an answering machine was already fast-fading into an irretrievable past, and I was inexorably becoming... something else.

We can study the RSS to learn what I was now doing, and in the process of learning that, we can learn how the pad was built.

How the steel was designed, fabricated, delivered, and erected.

Where it came from, where it was going, how it would get there, and what it would be doing, once there.

By now Richard Walls had discovered that I possessed some kind of innate eye for things. That I could, despite being a completely untrained ignoramus, look at structural steel blueprints and make thorough and accurate sense of them.

That I could look at the multi-hundred page set of insanely-complicated blueprints for the Rotating Service Structure, and, through some deeply-mysterious and unknown gift, find errors!

Errors that had escaped the attention of everyone else who had looked at the same drawing, before I unfurled it on to the makeshift drawing table we had in the middle room of the Sheffield field trailer, and started examining it.

I was at a launch pad, and I wanted to know everything, and sometimes, in the process of trying to understand everything, you find yourself unintentionally stumbling upon parts of everything that do not quite seem to go together properly. Do not quite seem to add up properly. You find yourself stumbling upon errors as you seek to find out, "What's this thing? Where is this thing located and what's it connected to? What's this thing here for? How does this thing work? What's this thing do?"

How something like this might have come to be, I shall never know. It just was, that's all.

And once we finally came to the incredulous realization that it was real, and that it came in through the door with me every single morning I arrived for work, and it was not just a one-off fluke, and that it very definitely was, RW and myself both instantly latched on to it, put it to the very best use on the job that we could, and worked as hard as possible to feed it more, not quite knowing if it might grow, how it might grow, or where it might grow.

It was more than enough to know that we had something, and beyond that it would not do to question things too closely.

And so I found myself being tasked with tracking the steel.

At Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B, on the Kennedy, by-god, Space Center, Florida!

Once a Great Thing like the Space Shuttle is chosen and committed to as a system to build and operate, an awful lot of things need to be worked out in order to bring the imagined concept from its initial state of existing only in the minds of the people who would like to implement it, to its final state of existing in the form of fuel and metal sitting on top of a launch pad, fuming and hissing, ready to fly.

And aside from the flight vehicle itself, the most important thing is the launch pad that it sits upon, where the payload it will be carrying into space is placed inside of it, where the fuel it will burn gets pumped into its tanks, and where the crew that will fly it walks out on a narrow steel catwalk, crawls through an open hatchway in its side, and straps in to their seats.

Things proceed in rigorous order.

What the Space Shuttle is supposed to do, with the allotment of money that is given to build it, dictates everything else.

Its desired size, lifting capacity, flight rate, overall performance envelope, and a million and one other things all get decided upon, bearing in mind that money money money drives the entire system, and that which gets built can only get built if there exists sufficient funds to do so, and in the absence of sufficient funds, nothing happens.

Politicians, managers, and designers all embark upon a crazed half-dance, half-battle, pushing and shoving, for and against each other, all trying to gain the upper hand and get what they feel best solves the problem, and you must always keep in mind that the problem most-often has nothing to do with flying in space, and everything to do with building personal fiefdoms and power blocs, fighting turf wars, wheedling money from clenched fists, desperately racing against calendars and ticking clocks, keeping allies happy and enemies at bay, and no end of other social considerations.

The Space Shuttle was a product of the social landscape in which it was designed and built, and social considerations took precedence above all else.

And at last, something is decided upon, and work is commenced.

Dirt is turned and metal is bent.

The hands of the politicians, managers, and designers are no longer anywhere to be seen, and now its in the hands of the foundrymen, the computer-programmers, the chemists, the machinists, the ironworkers, the engineers, and everyone else who's hands must get dirty, figuratively or literally, in order for anything to take shape in the real world.

And things start happening.

The Shuttle has been given a final design, and now everything else which is required to support it gets designed, in precise agreement with the particulars of the Space Shuttle.

And looming large on that landscape, stands the launch pad.

And the iterations of design cascade downward, with each final design dictating the particulars of all that must work with it and work for it.

Until you reach the very bottom of the cascade.

Where individual things like bolts are specified, all the way down to diameter, length, cut of thread and shank, coating, and the material from which they will be fabricated. Each bolt sees a different load, and each bolt must be able to take that load, be it tension, or shear, or torsion, or vibration, or environmental factors which may induce corrosion, or any number of other arcane considerations, all of which must be accurately foreseen and accommodated, lest the bolt fail, and catastrophic results ensue.

Where steel beams leave the drafting tables they were created upon and come to real-world life in dim noisy shop floors where hot-rolled structural shapes enter one end of the building, commonly in forty-foot lengths, rough, sometimes covered in mill-scale, and go out the other end of the building as precisely-cut lengths of steel, drilled, fitted, welded, bolted, painted, and labeled with piece marks in white chalk showing their exact name or part number.

Elsewhere, three time-zones away, the Shuttle itself is beginning to take shape, and the launch pad it will rise into the sky from must be ready when it arrives.

And this is where I come back in to the picture, and where the photograph at the top of this page comes back into the picture.

What the hell is this thing, anyway?

It's a box on wheels.

It's a facility for reliably and safely handling a variety of high-explosives, some of them pumped in bulk quantities at temperatures well under 400 degrees below zero, Fahrenheit.

It's a place where hundred-million dollar pieces of equipment are placed inside of multi-billion dollar flying machines.

It is a high-precision test and instrumentation workstand.

It is likely bigger than the last hotel you stayed in, and it rolls around across a gash in the concrete that's large enough to swallow a different, somewhat-smaller hotel.

It produces industrial-scale quantities of air that's cleaner than the air in a hospital operating room, and is itself, on its inside, cleaner than an operating room in a hospital.

It safely handles alarmingly-toxic and corrosive liquid propellants that are reactive enough to set rust on fire.

It can lift, on end, a railroad-boxcar sized Canister weighing upwards of one-hundred thousand pounds, over eighty feet above the ground and rigidly secure it in place, vibration-free and contamination-free, where it can then be opened up and worked with, using a gigantic and extraordinarily-complicated, six-story tall machine called the Payload Ground Handling Mechanism.

The RSS is so much more, and it does so much more, that I could not possibly list it all and must stop trying here and now.

It has a near-twin, located a little more than a mile and a half down the road from where it stands, which was built first, but aside from that, it is unique in all the world.

There is nothing else like it.

Anywhere.

And it was constructed and held together as an enormous steel framework consisting of tens or even hundreds of thousands (I do not know the exact number. Not even close. I never counted them all. All I know is that there were a lot.) of individual pieces of steel ranging from something you could hold in your hand, all the way up in size to a gigantic all-welded truss, one hundred and fifty feet long weighing roughly 150,000 pounds, and all of the individual pieces which made up that steel framework were fabricated by Sheffield Steel, who I now found myself working for, as if in a vivid dream, and then delivered to the pad, and somebody had to keep track of it all as it was offloaded from the flatbed semi-trailers it was delivered on, and that somebody was me.

Steel would be fabricated at the Sheffield shop in Palatka, Florida, on a schedule that would allow Wilhoit to proceed with the erection in a sensible sequence (things holding-up and supporting other things would be fabricated and delivered, within reason, before the other things that they were holding-up and supporting got fabricated and delivered), and it would all show up at the pad, neatly stacked for shipment on the flatbeds in loads occasionally weighing upwards of 50,000 pounds each, consisting of a bewildering hodgepodge of various-sized and various-shaped things, that, every last one of them, had to be located, identified, and ticked-off on a shipping list that was prepared at the fab shop and came with the delivery of steel.

Enter James MacLaren.

Who would have his own copy of that shipping list, and would be sent by Dick Walls up on top of the pad, where the delivery truck and trailer would be parked, and a crew of Wilhoit's ironworkers would work with their crane operator to place choker-slings or hooks or whatever else might be required on the delivered steel, lift it off the flat-bed, and place it in the shake-out yard, usually on cribbing lumber, but not always, where it would lay until it was time for the crane to pick it back up, and this time lift it into the sky where a gang of ironworkers was waiting to connect it to the growing structure.

And everyone had a separate job to do, and everyone worked with and around each other, and the whole effect was similar to perhaps a symphony orchestra where each musician played different notes on different instruments at different times, sometimes together with all the other musicians, and sometimes solo or by two's and three's, and all of it conducted and organized for greatest harmony and efficiency, by people who had to keep an eye on the overall progress of things as a whole.

Keep in mind that in 1980, up on the pad, MacLaren was the village idiot, and may very well have been the stupidest musician in the whole orchestra, but that didn't keep him from trying, and doing his very best as he did so.

RW was very careful to keep me out of things that I might, through ignorance, run a chance of fucking up, and so, at first, I was the schmoe who kept track of the deliveries. This was simple-minded enough work to entrust to me at the time, and I was extraordinarily diligent in not wanting to fuck it up, despite the simple-mindedness of it all. It was a definite step up from being an answering machine, sitting in a godforsaken trailer, driven half-mad with boredom, waiting for a phone to ring that, on certain days, might only ring two or three times during the entire day, but in the larger scheme of things, not a very great step up. And also, as a quite-unintended side effect, tracking the steel deliveries bestowed upon me a phenomenally-intimate familiarity with every single piece of steel in the whole tower.

Every.

Single.

Bit.

Of.

It.

And I would rub shoulders with grouchy, gruff, and grizzled old ironworkers up in the shake-out yard, with my clipboard and my copy of the shipping list, and I would poke around through the large and complicated pile of loose iron on the ground, looking for cryptic markings in white chalk on the individual pieces, that I could then match with the same cryptic nomenclature on my shipping list, and if perhaps I espied "364B11" on a piece of iron, I could then run a yellow highlighter across that item on the shipping list, and in that fashion, Sheffield Steel's launch pad people could be assured that A.) The piece had been fabricated in the first place, and B.) had been successfully delivered into the hands of the ironworkers up on the pad, who would be hanging it up in the sky somewhere at some point later on in time.

And a cultural shift has already occurred here, and I'm guessing you haven't even noticed it.

Up on the pad, in the presence of the ironworkers (who I respected deeply, and who often enough exuded an aura of sufficient fearsomeness as to cause me to want very much to not cross any of them), the very selfsame steel that was fabricated and delivered by Sheffield had now become iron. You did not speak with ironworkers about steel, you spoke with them about iron, and to do otherwise was consciously and deliberately cut yourself off and away from them, culturally, in a way that created a distance between you and them, and since I did not want to cut myself off, I very quickly learned that, when in Rome, do as the Romans do, and when with ironworkers, speak like ironworkers speak, and the path before you will become much smoother, and the distances between you and the ironworkers will become thereby reduced.

Why this cultural shift might have been so, and might have been so conspicuous, I could not tell you, because it is the way of people and there is no understanding people, but I can tell you that when you went from the file-cabinets and drawing tables in the field trailers, to the toolbelts, torches, and wire ropes up on the pad, you went from one world to another.

Two complete, separate, planets. With a wide array of stark differences, amongst which, the linguistic differences being quite noticeable and pronounced.

And, me being me, having never visited either of these planets previously in all my life, I was profoundly fascinated with both of them, and sought to learn as much about them both as I might humanly be able to during my limited time as a visitor there.

And I mentioned earlier that a lot of this was going to be about the culture and about the people, and here we are, on a dew-covered Florida morning, to the sound of the big Manitowoc crane growling in the background and the shouted cursewords of the ironworkers filling the air all around us, learning about the culture and the people.

The shipping list.

With a shipping date of November 18, 1980.

I had been there exactly eight months and one day when the truck driver fired up his diesel and departed the Sheffield property in Palatka, bound for the Kennedy Space Center with 41,566 pounds of steel.

Page 1.

Page 2.

Page 3.

Page 4.

And there are stories to be told, and lessons to be learned, just by examining this bill of materials.

Let's give it a look, and see what's going on with it. Let's see if we can get it to help us understand how the launch pad was built.

And what it was built of.

And for.

And more still than that, too.

There seems to be some sort of pattern to the way things are named. Some sort of system. How might a thing like that work? What would it be for? Why would someone spend the money required to put in the time to go to the trouble to organize the names of things in exactly this way?

And it's marked-up too. Someone has taken additional time (and never forget that time is money and no money ever gets spent unless there is a reasonable expectation that the expenditure will either be repaid directly, with interest, or will prevent the loss of money elsewhere, that might far-more than offset the savings gained by not taking the time to organize things, just so) to group things together, and then give those groups further inscrutable names.

The "someone" who marked it up was me. This is my own handwriting scribbled across the pages of the shipping list. This was my own copy of this shipping list, and I still have it.

So what's up with that stuff? What's that all about?

And I can see right now that this will be a very long page in this series of photo essays. Perhaps the longest page of all. Of that, I do not, right now, know. But I can confidently surmise that more words, by the thousands, will pass us by before we're altogether finished with this page.

The shipping list has headers above the typed-in particulars.

"Units" "Description" "Weight"

Units seems simple enough to deal with, and is simply telling us how many of each individual item there might be found in this shipment, and a nomenclature of "6 pcs." under the Units heading is simply telling us that there are 6 pieces, and it's no more complicated than that.

Weight, too, seems simple enough to deal with, and the nomenclature for pounds is to use a # symbol, and space is saved on the list by so doing, and time is saved for whoever had to type the list up, on a typewriter, but why would someone go to the trouble to carefully list it all in such fine detail in the first place?

And another door for understanding another aspect of how things get done, building a launch pad, has just opened up unexpectedly, and since we're here, we may as well go ahead and walk on through the door, and see what's on the other side.

And we immediately encounter money, yet again.

And in this encounter with money, we discover that creations made of steel, things weighing literal millions of pounds, made up of tens of thousands of individual pieces, get paid for by the pound, in exactly the same manner you might pay for ground beef, down at your local grocery store.

Same process exactly.

With the difference being that you cannot set a piece of steel that might be thirty feet long, weighing 20 tons down upon the butcher's scale, so instead, you calculate the weight, and enter it into your bill of material next to the item it corresponds to, and simply read that calculated weight off, and you're good to go, then and there. The butcher's scale remains intact, and everybody's happy.

So. How might we calculate such things?

And the answer to that takes a little detour of its own, winds down a bit of a path, and then takes us were we need to go, in order to answer our question about calculating the weight of the steel that just got delivered to the jobsite.

Up to this point, there have been numerous reference drawings included in this as links that can be clicked, to show you the drawing being referred to.

And all over very many of those drawings, you'll find notations like 22"Ø x 264 or perhaps W27 x 178 or any number of other, similar, variants, next to the lines that show us where the structural members are, and you may or may not have even noticed them (they are ubiquitous, and your brain tends to rapidly tune out things that are ubiquitous), and even if you did notice them, you may or may not have wondered to yourself, "Hmm, what's that all about?"

Very well then, it has come time to get to the bottom of what that's all about, and how it might relate to our shipping list, and how it might relate to money, both of which things (and more), it very much does.

Engineering drawings can be monumentally-complicated things, smothered beneath a blizzard of lines, symbols, letters, words, and any number of other strange and wonderful things, and there exists strong pressure to minimize, to the highest degree possible, additional lines, symbols, letters, words, and other strange and wonderful things in an effort to leave the drawing which is by now crawling with such stuff, readable, by the poor schlubs who must work with it.

This is a serious concern, because a drawing, misread, can have catastrophic effects on lives and property, up to and including the loss of both, and so certain customs and standards have been agreed upon generally, and get used industry-wide, to try and keep things under control, and keep things comprehensible.

And the business of weight falls squarely under that heading.

So.

Our 22"Ø x 264 turns out to be a shorthand way of telling us that we have, in order, a twenty-two inch diameter pipe, which weighs two hundred and sixty-four pounds per running foot of length.

And our W27 x 178 tells us, using the same shorthand, that we're dealing with a wide-flange steel member which is twenty-seven inches deep, and which weighs one hundred and seventy-eight pounds per running foot of length.

Using this particular system of shorthand, you can pack an enormous amount of information into an amazingly small space, thus keeping your drawing from becoming dangerously cluttered and unreadable.

So.

Now that we understand that they're telling us exactly what kind of structural shape it is we're dealing with, and exactly what it weighs per running foot, it becomes simplicity itself, using third-grade arithmetic, to calculate the weight of our structural member by finding its length, which is also given on the drawing, by yet another ubiquitous item called a dimension line.

And now at last we've reached the place where we have sufficient understanding to see why the time and trouble was gone to, to place such a detailed list of weights on our shipping list.

We were getting paid by the pound, and in order to do that, we had to list it all. And not only that, by listing it per piece, we also were giving other people the ability to check our work, and make damn sure we weren't just making things up or maybe padding things a little, and would therefore be getting paid a fair rate for fair work done.

And it doesn't even stop there, either. With the weights listed for each piece, we were also letting Wilhoit's ironworkers know, in advance, what kinds of things they'd be dealing with while they were offloading the truck, and again, when the same material was lifted into the sky.

Yes indeed, Wilhoit had a copy of the shipping list, too. And they had their own guy, doing exactly what I was doing with it. Everybody had a copy of that damned shipping list, because everybody, from NASA on down, needed to know exactly what the hell was going on out there at the launch pad, every single day, and shipping lists turn out to be one of the very best methods by which you can acquire a very fine-grained understanding of things, as they occur.

And, inevitably, with projects of this size and scope, mistakes get made. Not many, but even one has the power to boomerang around on you and really hurt you, figuratively and also literally, and that is something that nobody wants anything to do with, and for that reason, when more than one person or group is tracking along with things, any time the results disagree... well then, now it's time go give things a closer look, and get to the bottom of things, and make good and damn sure we've got it right. So. More pairs of eyes translates directly into better vision.

Individual items weighing in the tens of pounds get dealt with much differently than individual items weighing in the hundreds of pounds, and differently yet again from individual items weighing in the thousands or even hundreds of thousands pounds each.

If you're an ironworker, and you've been dealing with stuff like this for half your life, you sort of develop a sense of smell about things, and just based on weight alone, you can jump way ahead conceptually in your planning, and not waste so much as one additional minute with figuring out things that you already know to be a fact, by gut feeling, planning out what you're going to be doing with them, and how you're going to be going about it as you do so.

And it turns out that there's a lot more to it than even that, but for now we can give it a rest, and it's more than enough to simply know that an awful lot can be figured out and made good use of, just by knowing the weight of each piece of iron as it comes off the truck and eventually goes into the sky.

And now we can turn our attention to "Description" and see if we can make any sense out of that one, ok?

Here we go.

Letters and numbers, all nice and organized in alphanumeric order.

And down the "shop drawings" rabbit hole we go.

Shop drawings. Also known as "detail drawings."

There are drawings, and there are drawings and they are not alike, and they serve different purposes, and they have different aspects, and even different names.

With structural steel, almost always, you find yourself dealing with the "contract drawings" and the "detail drawings" and just to dice it up a little, the "contract drawings" which are the originals, and which are created by the engineering department(s) that are tasked with turning an imaginary set of desires and requirements for some particular thing or program into some kind of real-world rendering that can then get built in the first place, and in the second place also won't get anything destroyed or anybody killed in the process of building it because of inefficiencies or mistakes in the basic design rendering itself. The "contract drawings" get specially marked up, and become the "erection drawings" and in the end, you use a set of erection drawings and a set of detail drawings as you proceed with the construction of your launch pad, or whatever else it might be that you're building. Both the erection drawings and the detail drawings are produced (with rigid adherence to multiple sets of phenomenally fine-grained engineering and design standards) by the steel detailer.

Oh boy!

Bear with me on this, ok?

I know it's complicated. I know it's hard to understand. And I know it looks like we're going to an awful lot of long-winded time and trouble here, explaining things we never asked about, nor cared about, when we decided to ask about, "How's the launch pad get built, what's in it, what's it made of, and what does it all do?"

So the detailer, working from the contract drawings, makes drawings for every single piece of steel so that the people down on the shop floor, the ones beneath the overhead bridge cranes, with the cutting torches, and the welding gear, and all the rest of it, can actually make the damn thing, and each of those drawings has an individual name, down in the title block somewhere, and that name usually takes the form of "D XXX" where "XXX" will be a number, and with something as big and complicated as a launch pad, there will be literal hundreds, or even thousands, of different drawings, thus resulting in names that include numbers in the hundreds or the thousands.

The "D" part of the name is simply shorthand for "detail drawing" so that people looking at the drawing can tell at a glance whether it's going to include information they're looking for or not.

If I wanted to know the precise configuration of an individual steel member which can be found in the structure, I would want to look at a detail drawing, and if I wanted to know where it would be located within the structure, I would look at an erection drawing.

And the detail drawings are kept in one pile, and the erection drawings are kept in another pile, and that way things don't get mixed together inappropriately, and people can find what they're looking for a lot faster than if they had to leaf through literal hundreds, or even thousands, of individual drawings, looking for some damn steel beam that goes by the name of "364B11" to give it a good scrutinizing and try to figure out why the miserable damn thing is giving the ironworkers up on the tower as much trouble as it is, with a set of bolt holes in one of its clip-angles that fails to agree with the corresponding set of bolt holes in the web of the column that it connects to.

People can save themselves one whale of a lot of time and trouble (and save the company an equal amount of money too, never forget), by simply going to the detail drawings pile and turning to drawing number D-364 and looking for beam number 11 on that sheet without enduring any further ordeal in the process. It's vastly easier this way and vastly faster, too.

Ok?

Good heavens! All this for just a stupid shipping list?

Yep.

All this. And more.

So ok. So now we're starting to get an idea about why things beneath the "Description" header on the shipping list are organized the way they are.

But of course, there's more.

There's always more, isn't there?

Yes, yes there is. There's always more.

Let's go pay more a visit right now, shall we?

I suppose. If you insist.

Oh yes, I insist.

Very well then, back to things with arcane names beneath the "Description" header.

Things with names like "FW1-P1" and "239B1" and "328D6-R" and "331M1 R/L" and "367C1" and "402KB1" and "233M6x" which all seem to be trying to tell us something, but what?

Ok. We've just learned that something called "364B11" was a steel beam, and there's our clue, right there.

On our list, anything that starts with a number is referring to a detail drawing number, and that covers almost everything, with the exception of FW1-P1, FW1-M1, FW1-M2, and FW1-M3, right at the top of page one of the shipping list.

And these would be things that would not be found on any corresponding detail drawing, because no detail drawing was required.

"FW" stands for field work, and is the heading under which bits of steel that might be required to prosecute some task or other, in the field, by ironworkers using torches, welding rods, drills, or what have you, get placed. Things that require no drawing to create in the shop. Things that do not occur on the contract drawings as individual specifically-called-out structural elements which required design engineering to specify, and instead are simply catch-all things, without which, some task or other, somewhere, becomes either significantly harder and more expensive to do, or becomes completely undoable.

And at some point management (most likely Dick Walls) deemed the thing in question to reasonably be expected to be a part of the contract, or perhaps just as a way of easing Wilhoit's path in a good neighbor fashion, and by whatever means, the thing showed up in the world that overlaps Sheffield's fabrication shop, the shop was told to furnish it, and so they did, most likely doing nothing more complicated than lopping off a piece of something with a cutting torch and not so much as even primer painting the lopped-off piece afterwards, and there was not enough else going on with it to specify anything further except how many of them there were, which is six of them, so six lopped-off pieces is what you want, and six lopped-off pieces is what you get.

And so here they are, on our shipping list, and on our delivery truck, marked in white chalk with "FW1-P1." and nothing more than that. "FW1" might refer to a list, with a written description of the item, but even that is not guaranteed. It could just as easily be referring to a phone call that Dick Walls made to Palatka, with a verbal request, telling them to toss this stuff on the next truck, which is exactly what they did.

"P" stands for plate, and a plate is a simple piece of flat steel, bare and plain with no further particulars about it. In this case, since there were a total of 6 pieces marked "FW1-P1" weighing a total of 75 pounds, each piece can only weigh twelve and a half pounds, which corresponds to somewhat over a square foot of one-quarter inch steel plate (which is exceedingly common stuff on a job like this but which also, do not forget, we do not know it to be), and at that point we lose all hope of knowing anything further about these six small pieces of steel, but at the time in the field, you can rest assured that somebody, somewhere was expecting to see them on the delivery, and needed no further information of any kind to locate them, lay hands on them, and put them to the use for which they intended them to be put to.

And the next three field work items are called out with the letter 'M' and 'M' stands for miscellaneous, and miscellaneous is just that and who knows what any of it might have been? Three individual pieces, weighing 64, 36, and 179 pounds respectively, and nothing more than that. Likely not plate. Perhaps short lengths of wide-flange, or perhaps channel, or tube steel, or any number of other unknowables.

Same deal exactly as with P1. Somewhere along the line, somebody in the field needed something to complete some task or other, or perhaps to use as raw material in some way, and the item in question was cut to size in the shop, (or perhaps it was just picked up loose, from the pile of drop left over from the fabrication of something else and measured, as-is), listed, tossed on the truck, and here it is, at the pad.

Very often, 'M' stuff winds up being miscellaneous assemblies, some of which can be quite large and complex, but that is definitely not the case for our field work pieces on this shipping list. Assemblies require drawings in order to fabricate them, and field work pieces, by definition, do not fit that description, and do not have any associated drawings that go with them. Elsewhere on the list, we encounter "331M1 R/L" and these very much are assemblies of some kind, fabricated to whatever particulars as may have been found on detail drawing D-331, weighing in at a respectable-enough 1,500 plus pounds each.

And that's how that gets done.

Going down the list, now that we already know what 'B' and 'P' and 'M' stand for, let us finish up with the knowledge that 'D' stands for diagonal, as in diagonal bracing, 'C' stands for column, which should be self-explanatory, and 'KB' stands for knee brace, which consists of a shortish beam with a diagonal affixed to its far end, away from where they both connect to some vertical member somewhere, some column somewhere, in a manner wherein the far end of the beam, away from the column, is being braced by the diagonal beneath it, to make it stronger, so as it can carry its intended load safely and securely. Knee braces can be found all over the place, especially in conjunction with runs of piping or cable tray which they form part of the support framing for, and as such are worthy of getting their own special name. 'R/L' stands for "right" and "left" and tells people about the opposite handedness (which we've already discussed previously) of the two different pieces (and please note, on the shipping list, under the "Units" heading, the number of pieces associated with any of the 'R/L' stuff), and keep in mind that this sort of thing might generally (but not always) be expected to show up in pairs on a steel delivery shipping list, but sometimes they don't, as is the case with our own list on Page 1, and why 328D6 was listed twice, with a '1' under the "Units" heading each time, once as a '-R' and once as a '-L' I'm sure I will never in my life know, but there it is, right there in front of us.

There's more, but for now, this should be enough.

Enough to get you started, anyway.

And now, at last, we come to the final bit of inscrutable stuff on our shipping list, the marked-up groupings of things.

And now, at last, we're going to start learning exactly what sorts of components and subsystems our launch pad was made of, and what each thing it was made of did, and why it was where it was. And this mark-up stuff is in my handwriting and we have reached a point where I was by now sinking my teeth deeply into all of that "What's this thing? What's this thing here for? How does this thing work? What's this thing do?" stuff which drove me, as I walked, disbelieving, thunderstruck, through a landscape which I would never, in my wildest dreams, ever have imagined myself walking through.

Phew!

Never thought we'd make it this far, did you?

I was having my own doubts about it too, truth be told.

The markups. The groupings.

Field Work

RCS

PBK 3K70D

HFL 100-211 3K65Q

VEH ACC 3K53D

SRB ACC 3K56D

CATW 211-220 3K65P

SQ PLF 3K65R

CATW 163 3K65L

TOP TRUSS

CATW 211 3K65M

Ok, what's this?

It all comes down to places, pounds, dollars, and the contract.

It all started out as a NASA contract (one of many), to get themselves a nice new launch pad built, and the original, government, contract documents had a name, and that name was NAS10-9655, but beyond that we shall not go. Or at least not right now, anyway.

This page has run too long already, and I'm not going to be delving into the contract right now, but please keep in mind that all roads lead back to the legal binding agreement between parties, which is the contract, and how that contract is organized.

At some point further on, I'm going to have to delve into it, but not now, ok?

Too much. Not gonna do it.

The funny "3K..." numbers out at the ends of most of the lines are Sheffield Steel's in-house contract stuff, and constitute divisions in the payment schedule of that contract, and are kind of self-referring insofar as they point back toward where and what each grouping might be on the tower, on the RSS, and the RSS is what we're interested in, and we'd like to know what it's made of, what it does, why, and how it all fits together to create a unified whole, a Space Shuttle Launch Pad.

Oh boy, here we go.

But I'm going to be keeping this simple right now. I'm just going to be hitting the high spots and then moving on.

All of this stuff will be visited again, multiple times and in much greater detail, but for now, we're just going to be kind of waving at it as we go by, no more than that, and down the list we go!

"Field Work" is already something we know enough about, and can move on.

"RCS"

Reaction Control System.

Which was a very critical, very dangerous, and very complicated system of small rocket motors which used hypergolic propellant to orient the Orbiter, once it had departed the sensible atmosphere and could no longer be controlled via the use of its aero surfaces. "RCS" in the usage of the construction of the launch pad always refers to the forward RCS thrusters, which were all located in the Orbiter's nose, and never to the corresponding set of aft, RCS thrusters which were located in the area of the Orbiter's tail.

Why this peculiarity of nomenclature, with aft requiring specific mention, but forward just being more or less assumed, I never learned. Just another one of those culture items, manifested linguistically, and when in Rome, and you say RCS, everybody knows you're referring to the forward RCS stuff, and if you wanted to refer to the aft RCS stuff, you'd say "ARCS" and that's just the way we did it back then, and you get used to it, and you quit thinking about it, until forty years go by, and all of a sudden you find yourself wondering, "Why? Why did they do it that way?" And no answer is given, and that's that.

So ok. So for the purposes of building our launch pad out of steel, the grouping of "RCS" on the shipping list refers to the steel from which the RCS Room was constructed, and the RCS Room, is a bit of a misnomer, it being house-sized, three-stories tall, with a floor plan that's pretty close to 30 feet by 30 feet square, so really, it's a big box, and can only be considered a room when it gets compared to the much larger RSS it sits on top of, being one of the things that gives the RSS such a distinctive look, with the RCS Room sitting there partially-cantilevered up on top of everything else with a weirdly-offset big door on its front side, hanging over the open space below it.

Here it is here. And here it is here, again, but keep in mind you're looking at it from behind in this view, so opposite hand. And here it is here, one more time, just so you've really got a feel for it. In case you haven't guessed by now, we're really going to be seeing a lot of the RCS Room and its environs later on, different times, different reasons, same place, RCS Room. So kinda make a note about that one, ok?

"PBK"

Payload Bay Kit.

To begin with, this grouping of steel members was actually called "Payload Bay Kit and Contingency Platforms" but that whole "and Contingency Platforms" thing was over-long and never got explicitly written down as a separate item on any of the paper we produced and consumed, and the Contingency Platforms steel was always included as a part of the overall PBK and Contingency Platforms whenever it was being dealt with on the job, and for that reason it just got shortened to "PBK" and that's it, that's all you get. Also, the "Contingency Platforms" portion of this steel was tiny, it being just a single small flip-up, and compared to the overall category, it really wasn't worth the time and trouble to even mention it, anyway, although it's job was quite significant as a separate and distinct kind of thing and it was treated accordingly.

Ok, fine.

So what is it?

Well... a Payload Bay Kit turns out to be modular frame that can be placed inside the rear end of the Space Shuttle's Payload Bay adjacent to the OMS Pods, acting as a specialized pallet, which carries additional propellant tanks, thereby extending the capabilities (read burn time) of the Orbital Maneuvering System motors, which are what's used to make significant changes to the altitude or inclination of the Shuttle's orbit, and which are also used as brakes, to slow the Orbiter down and take it out of orbit and bring it back home. Needless to say, the OMS motors are a pretty important item. Here's the oldest document I could find, from 1974, which makes reference to a Payload Bay Kit. And here's some more, from 1991, with a bit of a drawing of the "Kit" itself, of very low quality unfortunately, to give you a bit more overall understanding.

As for the PBK structural steel that we furnished, it was a set of fairly-involved platforms down near and extending below the main floor level of the RSS at elevation 135'-7", but it was all external to the PCR, and more or less constituted part of the face of the RSS, down at that set of elevations.

Some of it was pretty tricky, and it included regular platforms, flip-up platforms, a fair bit of framing steel to hold it all up, and above the platform grating, there was a pretty long monorail beam with a particularly-weird curved end to it which was hinged, so it could be lifted up, out of the way, to clear the side of the Orbiter during mate and de-mate operations with the RSS. Again, we'll get into more detail with this steel later on, and right now, we're just hitting the high spots, so that's all you're going to be getting on it here and now, ok? Stick around, it'll come back. Several times, in fact.

Take a look at it from the side, here.

And again, here as an isometric view, and in this view, the Contingency Platform Flip-up, which gives access to something called the "50-1" Door on the left side of the Orbiter, is not even shown as existing in any way. I've got a feeling that this isometric-view drawing was created extremely early in the design process before they decided they might even need access to that 50-1 Door when the Shuttle was out on the pad, and it was left as-is, unaltered, even after the Contingency Platform was added on to things later, although that is strictly conjecture on my part, and I have no proof of it.

And, while we're here, that word, "contingency," carries with it an aura of unease, of calamity, and of very unpleasant things indeed. In NASA-speak, "contingency" is one of those words they use to keep from having to use other words. Words like "failure," or "killed," or "disaster," or "catastrophe," or any number of other words associated with the sorts of things that can go badly wrong, unexpectedly, without warning, when you're dealing with rockets, and that goes doubly so when the rocket you're dealing with is carrying people. Whenever you see the word "contingency" the hairs on the back of your neck should start standing up, even if you cannot see that anything is amiss, any where, in any way. It's not always that dire, but oftentimes it is, and it should be treated as a word that holds special power and special meaning, because that's exactly what it is.

The pair of Contingency Platforms gave access to a pair of somethings called the "50-1" Door and the "50-2" Door which are found on either side of the Orbiter's fuselage near its tail, and the these Doors are hatchways that provide access to the engine compartment, and if you find yourself requiring access to the engines while you're out on the pad... well then...

This is a place that needs to be done and buttoned-up good, before you roll to the pad, although these same doors were also used for servicing the Aft Propulsion System (the OMS Motors plus the Aft RCS Thrusters), too, so it wasn't necessarily contingency-driven access, at all times.

The days grind on and turn into years. The years roll by. And day in, and day out, you're doing your job, and a job is something that all too often becomes rote, repetitive, banal, reflexive... and awareness fades. We lose our awareness, no matter how hard we try to hold on to it. But in some jobs, that loss of awareness holds grave danger, exquisitely well-hidden, for ourselves, and for those around us, and even, sometimes, those in distant places. And when your job deals with unforgiving things...

It can be bad.

It can be very bad.

We can never forget where we are, when we're on the launch pad.

Lest the Hand of Fate reach into our lives... and alter them.

"HFL 100-211"

Hangers, Framing, and Ladders, elevations 100 to 211 feet.

Quite the mouthful.

And this one is a sort of catchall for a lot of stuff scattered across the full vertical extent of the RSS in the more or less open area between the Hinge Column and Column Line 2. It's all about two kinds of Crossover Platforms and their associated access ladders and supporting structural hangers and framing, which there is a bewildering array of for each kind of crossover, for a bewildering variety of purposes, but all of them are associated with the areas at and near the Hinge Column. In addition, there is a separate and distinct set of platforms included in this grouping with their own associated access ladders and supporting structural hangers and framing, near, but not quite abutting, the stuff over by the Hinge Column, and this bunch of stuff at least had the good grace to stay put and not move around all over the place. But the whole thing, both sets, is what a lot of the ironworkers would call "junky iron" and none of it is heavy and all of it is extensive and complicated, and it all has to go together just so, and... it was a bastard to deal with, in the air and on the drawings.

Since the whole goddamned steamship-sized RSS rotates through 120 degrees of travel, through one full third of a circle of travel, the vast load of things it carries with it, including one hell of a lot of ducts, wires, cables, tubing, and piping coming up or across from the pad itself over through the FSS, will be rotating right along with it. Which is all well and good, except, remember, the FSS (and the Hinge Column too, except for the upper and lower bearings), doesn't rotate, and is fixed firmly to the ground, and somewhere in there you're going to have a place where large heavy objects snaking across from one tower to the other as they go past the Hinge Column, are going to be needing rock-solid support at the place where they're going to be bending, flexing and rotating as the RSS grandly swings around from the de-mate position to the mate position, and back again, even as the FSS and the Hinge Column remain firmly immobile the whole time.

Just inboard on the RSS from the Hinge Column platforms that did not move, were the moving RSS platforms that picked up and carried all those ducts, wires, cables, tubing, and piping coming over from the FSS. These moving platforms were separated from the non-moving platforms by a narrow gap that you might just barely be able to put the flat of your hand into, except that the gap was covered by a 16-gauge curved strip of stainless steel, to keep things from getting into that gap and becoming snagged on it in some unpleasant way.

HFL 100-211 concerned itself with the Crossover Platforms, plus what amounted to a glorified vertical run of pipe supports, but for hypergol which is a word that we're going to need to learn how to become properly terrified of, but not right now, and it was a little farther inboard on the RSS away from the Hinge Column than the Crossover Platforms, and both sets of items were part of the RSS, and moved around with it, and it also included the stuff that was attached directly to the Hinge Column, which did not move around.

And all of that stuff was our Hangers, Framing, and Ladders steel, and it was quite the snarl of different stuff, and it's impossible to visualize all of it in one go, so it's broken up into two different sub-sections, the Crossover Platforms portion of which is shown here, and the Hypergol portion of which is shown (On the Pad A drawings, and you might want to get used to checking the title blocks on these drawings to see if it says "79K14110" which is Pad B, or "79K04400" which is Pad A, and which is also roughly 5 feet lower, which means all the listed elevations are wrong for Pad B, and you really do need to try your best to remember because one day it's going to come up on you unawares and get you!) here, and again here, in greater detail so you can see how it was attached to the rest of the RSS and also get a pretty good look at how a Caged Ladder was constructed, and if you're not sure where you are with the heavy stuff that holds it all up, well then, here's the Hinge Column, Struts, and FSS, once again, just to kind of give you some perspective on where you are in the larger scheme of things, structurally.

And since we're here, I need to mention that the second view of the hypergol stuff, on Drawing 79K04400, sheet S-79 (the 'S' standing for "Structural") also just happens to be an excellent example of a section cut, which is what the yellow-highlighted stuff to the right is being shown as, said section being cut through the Elevation View which is the yellow highlighted stuff to the left, and which, if you look close at the elevation view, you can see a symbol just below the tail of the 'p' in the word "Hypergol" in my labeling up above it all, which kind of looks like a circle, with a largish letter 'B' in its top half (which is rolled over on its side, just to make things interesting), with "S79" underneath it twice, and the first one of those S79's (which would be on the left, if only this thing was right-side-up) is telling you which drawing that the section cut comes from, and the second one of those S79's tells you which drawing you can go to, in order to see the section cut, and in this case they both happen to be the same drawing, but that's not always the case. That 'B' up above, is telling you to look only at section cut 'B' on the drawing you've been sent to (and again, you don't have to go anywhere this time, since it's all on the same page),and coming down from that symbol, there's a very long vertical line that extends all the way down to just past the very bottom of the yellow-highlighted stuff on the left side, and at the very end of that line, there's a funny-looking sort of tail, or maybe half an arrowhead split longways (which is exactly what it is) and that split-arrowhead is pointing in the direction you will be looking in, from the point of view of that whole line attached to it above it, which goes all the way back to the circle thing, the symbol, with the 'B' in it, up at the very top, at which point you can then go look for (on the drawing number in the right side, below that 'B') "Detail B" on that drawing, and get a look at the cross-section which they want you to see, so you can tell how this stuff is built, looking at it from the given direction of the section cut.

Phew.

But try your best to get with the program on section cuts, ok? Once you get 'em figured out, and understand how to use 'em, it suddenly becomes like having a second pair of eyes, and they're X-Ray eyes, and... well, yeah, sometimes it's nice to have a spare set of X-Ray eyeballs that let you see what things look like, right through solid metal and stuff.

This whole area between Column Lines 1 and 2, from the bottom of the RSS to its top, was just nasty, insofar as it was neither here nor there, was neither fish nor fowl, and it was crowded with a bunch of crap, and some of the crap it was crowded with was surging inside, filled-up with insanely poisonous, corrosive, and explosive, rocket propellants at significant pressure, and that stuff is far more than bad enough to begin with, being pumped through the nice solid straight runs of extraordinarily-special piping they make for the purpose, and now here we're going to have to be pumping this stuff through flex connections, and flex connections have the same properties of any other moving mechanical system insofar as they can wear, and if they wear out, well then... whatever was in them, is now out of them, and things will go straight to hell RIGHT NOW if a thing like that happens, so the areas where the flex connections are located must be accessible by the technicians who inspect them on a regular basis, and who also will have to have room to work on them, if it's Routine Maintenance Day, or if the inspections reveal that things are beginning to wear out, and there's no room for an elevator over here, so it's all caged ladders, and really, the whole place is a nightmare, but you'd never know any of that by looking at it, 'cause it just looks like a bunch of stupid out-of-the-way platforms crowded with a bunch of Mystery Pipes and it's all connected up with a bunch of caged ladders.

And yeah, I never liked any of this stuff.

And as one more 'while we're here' this might be a good time to let everybody know that a "hanger" is a vertical steel member which is supported from its top, in tension, hanging, as opposed to a "column" which is supported from its bottom, in compression, resting on top of something.

Both have jobs to hold up other stuff, and in that regards are identical, but the action of forces upon them, is different, and for that reason, they are treated differently, and get different names.

"VEH ACC"

VEHicle ACCess Platforms.

Which is another grab-bag of stuff, but at least this one is pretty cool, since it involves providing various personnel access to the Space Shuttle itself.

The largest task performed by the RSS consisted in carrying and enabling the PCR to do its task of servicing payloads, but the Space Shuttle was an amazingly-complex and ramified thing, and there was plenty more that might need to be done with it, to it, on it, in it, and around it, while it was on the launch pad, and anything that fell under any of those headings would of course need to be accommodated in some way, and the Vehicle Access Platforms were just one manifestation (and a quite multifaceted one at that) of getting those sorts of things done, on the pad.

There's a lot of overlap with other systems in this one, and for the purposes of the steel deliveries Sheffield was sending to the pad, we can ignore Vehicle Access Platforms at or above the Antenna Access Platform at elevation 198'-7½" and at or below the main floor of the RSS down at elevation 135'-7" and once you've done that, you've narrowed it way down, to just a few items.

Just from a "Where is it?" point of view, there's not very much to this one at all. Here it is, here, opposite hand.

"SRB ACC"

Solid Rocket Booster ACCess Platforms.

The SRB's provided the lion's share of the push, during the first part of the uphill climb to orbit, but compared to the Orbiter (with its own set of engines), the SRB's were simple enough things, for certain definitions of "simple."

At the pad, there was not a lot that could be done with them, and access to service them was correspondingly reduced, and really, the only place on the whole RSS providing any access to the SRB's at all, was all the way up near the tops of the SRB's, and these platforms provided that access on either side of the RCS Room.

The platforms themselves had a fairly simple appearance at first glance, from a distance, but a closer look reveals that they were surprisingly complex, and consisted of a platform inside a platform that you can see highlighted on Drawing 79K14110 sheet S-68, and the inner platform rolled in and out, permitting it to be backed away from the SRB when not in use, and then close in to a point of near-contact with it whenever the SRB required hands-on attention from a technician.

The mechanism, which you can see on 79K14110 sheet S-69, that ran the inner platform in and out was hand-cranked, with a delightfully old-fashioned heavy cast iron handwheel that you turned, and it gave quite the satisfying feel of solidity in motion when you played around with it.

79K14110 sheet S-68 also shows a little "step-up" platform that sits on the end of the Extensible Module, but I never saw the one shown on the drawing out there in its working position, even once. It was always fastened down to the grating, sitting off to the side, over next to the RCS Room at the corner of the SRB Platforms Access Catwalk where it took one of its funny turns on its way out to the actual SRB Access Platform. A second version of it showed up later, and we'll get to that, but not now. You can see it in the photograph that heads Page 65, but I'm not going to jump you forward to it, 'cause you're already dealing with waaay too much for me to be adding anything else to what you're dealing with right now. It provided the only access for the techs to work, and to close out prior to launch, a smallish removable panel that was located very near the top of the SRB. We'll revisit the SRB Access Platforms later on, but for now, you've got enough to go on, with this stuff.

Underneath the actual platforms, holding things up, was a difficult cantilevered support bracket made out of sturdy pipe that had to be very carefully cut and fit in the shop and then welded up as-is and then delivered as a single piece to the jobsite.

The ironworkers handled all of it like a breeze, but trust me, this whole apparatus was very much a heavy, awkward, difficult, and just generally fussy thing to get right, up in the air, hanging off the front and sides of the RCS Room, with nothing beneath it except for a gut-churning unimpeded seventeen-story free drop all the way down to the cold hard concrete of the pad deck.

After I had departed the pad for the last time, the SRB Access Platforms underwent a major modification, completely rearranging their construction, aspect, and look, and most of what you see when looking for images on the internet, that include them, shows the altered configuration, which can be confusing if you're not paying attention to that kind of thing.

"CATW 211-220"

CATWalk, elevations 211 to 220 feet.

This was one of the main pathways between the FSS and the RSS, and this one was the highest one, providing access from the FSS at elevation 220' over to the roof of the RSS at 211', which means the whole RCS Room and Hoist Equipment Room area up there, where there was a lot of different stuff located.

This crossover catwalk was for personnel access between the FSS (which had a set of elevators that went all the way to the ground) and the RSS (which had no elevator to the ground, necessitating at some point people were going to be walking across from one tower to the other), and these personnel accessways in no way, bore any resemblance to the other Crossover Platforms which you have already been introduced to.

Completely different concept with these things, and it made them tricky, and they were tricky to fabricate and build, and they were tricky to even understand, just looking at them, because of the refusal of the human mind to so much as consider the fact that a cyclopean steel construct on the scale of the RSS could ever be anything except a part of the landscape, in the same way that mountains are part of the landscape, and mountains do not move around across the goddamned landscape and human brains just will not agree to having a thing as big and solid as the RSS just go rolling around somewhere, on its own, not only to a different location but also rearranging its very orientation while it was doing so.

When you were up on the tower, your brain regarded the the RSS in exactly the same manner that it might regard a mountain, that had, one fine morning, for no good reason, not only picked up and moved, from here to there, but had also, impossibly, done a third of a full pirouette while doing so.

Nope. Can't happen. Never did happen. Never gonna happen.

Even when you knew better for a fact, yourself, up to and including having seen it do so with your own eyes.

The psychology of the RSS is marvelous stuff indeed, and I'm sure I'll never understand any of it, but I certainly do understand the disorientation caused by the damn thing in regards to these personnel access catwalks that went between the FSS and the RSS.

And you had to mind yourself when you were up there.

Even when you knew full well what was going on.

Because your brain, which was having none of it, would send you over the side if you let it, and up at elevation 220, going over the side is not a good idea.

Here's your first introduction to this less-than-straightforward stuff, here, mostly for the FSS side of things, on one of the architectural drawings, Drawing A-6, and please note, as-shown, the RSS is in the Mate position, but when we were building this stuff, the RSS was in the de-mate position, which of course only adds to the fun, when you're cracking your brain over these things, trying to make sense of them. But it's a start, so at least we've got that.

And here, on structural Drawing S-5, we see the catwalk with the RSS in the de-mate position (or at least some of it, anyway), along with the non-moving framing that held up the part of it that was over on the FSS side of things.

And to see what's going on out of view of the two linked images you've already seen, over on the RSS side of things where the rest of the catwalk lives, you have to go to yet another drawing, here, and since the catwalk had to slope down from its initial starting elevation of 220' over on the FSS to elevation 211' which was what the roof of the RSS was, you would pass through two different drawings to do that, which means you started out by looking at it on structural Drawing S-42 (which is the higher elevation) but then had to finish off trying to figure out what the hell was going on with this thing by looking at the other part of it, here, on Drawing S-40 (which, of course, is the lower elevation), and... GAH!

And the drawing quality is crummy, and doesn't that just improve things oh-so-very-much, and yes, crummy drawing quality was something we had to deal with at the time, too, and when you take one of these big 'F' size drawings with you up on the tower, and it's flapping around all over the place in the wind trying to tear itself in half, and it's all crumpled up in exactly the wrong places from where you tried to fold, and then unfold it, and maybe somebody spilled coffee on it somewhere a couple of weeks ago, and you've already been scribbling on it to the point where you're running out of room for more scribbles, and the ironworkers haven't laid down any grating yet 'cause the framing's off in a way that doesn't make any sense, which is why you're up here with this damn drawing trying to figure this shit out in the first place, and you're hanging out over certain death on a horrifyingly-narrow piece of naked steel trying to keep the wind from blowing you off the tower while you're also trying to simultaneously read and write notes on the goddamned drawing that's blowing around all over the place, and now it's acting like it's gonna start raining, and....

This stuff can get hairy on you, and the penalties for getting it wrong can be astoundingly harsh in ways that nobody can foresee, and....

Yeah.

And never forget, the whole place is bigger than a soccer pitch stood longways on end, and the effect of the RSS being on wheels was as if somebody had decided that they needed to take half the soccer pitch and sort of cut it off away from itself, and move it around to the other side of the pitch, and then twist the moved part around by one third while they were doing it, and may as well go up nearly ten feet into the air while we're doing that (hey, why not?), and then have it all fit back together again so closely that one of the sideline benches, which was unfortunately sitting directly on top of the line they split everything along, before they moved it and twisted it and jacked it up, so half of the bench got split off and moved and twisted and jacked up too, and then have that miserable goddamned split bench fit back together again on the other side so closely, that somebody sitting directly on the split would never even notice it was there.

GAH!

And then, just for even more laughs and jolly fun, undo what you just did, with the whole four-million pound half-a-soccer-pitch, and then redo it, any old time whenever the hell somebody feels like it, and every single time, everything has to fit perfectly.

Sure. Why not? Let's go do it. Let's go do it now.

And we did.

So ok, so now that I've beat the hell out of you with this one, how 'bout we wrap it up all nice and neat (or as neat as this stuff, along with the reference materials I have to show it to you, can ever be gotten), and let you see a generalized overview of it all, FSS, RSS, Catwalk, Mate, De-mate, the Whole Works, using architectural drawing A-16 to give you a feel for the whole area up here.

Ok.

First, the whole place, FSS to RSS in the MATED position, as-shown on the unaltered layout of Drawing A-16, with colors and labels to let you see the bizarrely-crooked path that this catwalk had to take because of the way the RSS was built, hanging off one side of the Hinge Column, and the way it moved, rotating around the the Hinge Column.

Here it all is, here.

And please remember, this is NOT the orientation of things as we built them, and it is not the way our nerves and muscles and bones all sort of absorbed things during that process, as the way things are supposed to be. Make a note of the KEY PLAN, down in the lower right corner, just above the Title Block, to see how it's all oriented with itself, FSS and RSS.

Ok.

And now, I've doctored up our good friend Drawing A-16 to make it look (or at least as much as I could, anyway) like it looked as we were building the damn thing, in the DE-mate position.

And here all that is, here. And notice, pretty please, how I've even gone to the trouble to alter the damnable KEY PLAN, to bring it into agreement with the rest of the altered drawing, to let you see how four-million pounds of spinning RSS gets moved around in relationship to the non-spinning FSS, so as you might better understand this stuff, and also see it as we actually built it. And maybe while you're noticing all of that, maybe also notice that you are now taking a completely different path from the FSS to the RSS, and back again, along what has now become a completely different catwalk. Different. Catwalk. Same. Place. Because the RSS rotates.

And now, just for shits and giggles, I've attacked poor old A-16 again, and spun the whole works around, through one-hundred twenty degrees of rotation, to make it look like it was the RSS that moved, instead of the FSS, which is now sitting right where it originally was, north to the left.

Have a look at that one, here, just for laughs.

And also, maybe for a cold shiver or two, when we return to this place later on.

Here's another view of this catwalk, which gives us a much better feel for just how open and exposed this thing was, way up there, above the Hinge Column and Struts, and then mind that slope and don't slip when you're headed down to the RSS Roof, while you're a it, ok?

It wasn't always "just for laughs" up there.

Maybe make a mental reminder to yourself about that innocuous little yellow-highlighted "SAFETY CHAIN SEE S97" note with a triple-headed arrow, pointing in three different directions, over there near the Hinge Column, which shows up best on the RSS Mated, original version of A-16, and here it is again, here, just so you can go find it and remind yourself to remember it, ok?

Yeah, that's it. Be sure and remember about those safety chains up here on this catwalk, ok?

"Safety" chains.....

And now that we've entered the detailed world where we're getting close looks at things on the drawings, and now that you can be presumed to have by now gained enough savvy to start understanding these things on their own terms, I'm going to jump away from the items on our shipping list for a side trip over to the Main Floor area of the RSS, and the Crossover Catwalk which takes you there from the FSS.

This catwalk, which ran in a bizarrely crooked and multiply-sloping manner from one tower to the other is how everybody accessed the RSS and PCR.

Highest-traffic place on the whole set of structures. Number one. And not by a small amount, either.

When we're taking this catwalk to the RSS, we're heading Downtown. Straight to the heart of things.

It is a significant feature on the landscape, and even though it is, strictly-speaking, extraneous to our present discussion, it needs to get introduced into things, and there will come no better place and no better time for doing that than right here and right now, so let's do this, ok?

Same exact deal, conceptually, as our Crossover Catwalk from FSS elevation 220' to RSS elevation 211', but the execution of that exact same concept was, by necessity, very different in its physical configuration, and that was because it had different jobs to do along the way, and also because of where it was perforce located, deep within the Steel Forest which surrounded everything in this generalized area where you worked your way across, starting out by exiting the elevators on the FSS, then passing through the Struts, and then passing by the Hinge Column into the realm of the RSS proper, and then continuing to pass through even more thickly-forested countryside in the area, switchbacking along the sloping pathway between Column Lines 1 and 2, before you reached your final destination on the solid ground of the steel-bar grating and checkerplated expanse over on the main body of the RSS, at elevation 135'-7" beyond Column Line 2, all the way back on the far back side of it, near Column Line A, not so very far at all from the entrance door to the Anteroom, which is how you gained access to the Payload Changeout Room. Downtown.

And our job of understanding this catwalk will be complicated (but you can do this, right?) by the fact that the drawings of this area, for Pad B, are abysmal, and are actually worse than useless for the purposes of what we're trying to depict with this, very important, crossover catwalk as it existed when we built it, and for that reason, I have had to use the Pad A drawings, but those too are inadequate for the task, for their own reasons, which we shall not be getting into right now, and in the end, I wound up having to create a frankendrawing composed of body parts from here and there all sewn together to create a single unified whole, which shows things as they were when we were building this stuff, and we're just going to have to live with it, ok?

B Pad got the holy hell modified out of it, in more than one place, a few of which were quite large and extensive, and as a result, NONE of the drawings properly match what we're seeing in my photographs. So. I had to alter things, in order to bring them into better (certainly not perfect, but good enough will just have to be good enough) agreement with what you're seeing, which of course is what I'm attempting to describe and explain to you.

Phew!

Here's the worse-than-useless Pad B drawing for RSS elevation 135'-7" without comment, without explanation of why its worse than useless. It's bad enough already, without me further burdening you with those explanations, above and beyond the simple fact that for the most part, our catwalk is not even there on this drawing.

And if you want to see the damn catwalk on the Pad B drawings, well then, here you go, and we'll give you some of it anyway, and that's not very satisfactory either now is it?

And over on the Pad A drawing for this same place, for Downtown, (different elevations over on A Pad, so mind the elevations), things are better, but not better enough.

And so, because I was forced into it, I present you with.... FRANKENDRAWING for this area, and finally, on our frankendrawing, we can see things well enough to make proper sense of them.

And would you just take a look at that catwalk! It's all over the place! Complete with switchbacks, an intermediate stop to visit a Hinge Column Crossover Platform, another intermediate stop to visit one of the platforms that's part of the "HFL 100-211" which we've already discussed, up above, on this page, and no end of other twists and turns and sloping places, as we work our way along, trying to get from here to there. Trying to get Downtown.

And now that you have a sporting chance of understanding all of that bizarre "Darker Blue De-Mated" stuff over there on the far right side of things (Hint: It's our catwalk, over on the RSS), here's the rest of this catwalk, over on the FSS side of things, fixed in place, unmoving, shaded in red.

And we're never going to be getting a picture of this thing, because it was impossible to photograph.

Can't be done.

Had it been doable, you can rest assured that I would have done it.

Main accessway to the whole RSS.

And you think I would not have stopped and photographed it if I could? Do you think also that I did not scratch my head over this conundrum repeatedly, more or less every single time I was up on the towers anywhere near this thing with a camera in my hand, trying to find and angle, trying to get a sensible frame?

Nope. Not gonna happen.

End to end, this thing started out higher, over on the FSS side, and then wound up lower at its terminal end on the RSS.

And yet, because of the exigencies of the Steel Forest through which it wended its way, the first thing it did upon leaving the (higher) FSS, was to slope upwards!

And that's because of where it had to go along the way, and what it had to pass through along that way, and in the end, it was just impossible to get a sensible, useful, photograph of it.

You couldn't get far enough above it. You couldn't get far enough away from it. You could not fit enough of it into a frame to wind up with something that made any sense. No matter where you approached it from (and keep in mind that those options were severely limited), you could never frame it. All you would ever wind up with would be images haphazardly cross-hatched with the dark silhouettes of an incredible number of steel framing members, large and small, intertwined with an equally large number of cable trays, and other extraneous stuff. And threaded invisibly through all that, lurking unseen for the most part, it steadfastly remained blocked from proper view.

So no picture for you, alas.

You know where this thing is now. So ok. So from here on, in all of the photographs to come... be looking for it. Keep your eyes peeled for it, ok?

Best of luck with it.

But it was a really cool place to travel.

The 180 degree sloped switchback right in the middle of it, in particular, was somehow... neat.

I dunno. Can't explain it.

And it's broad blazing Florida Daylight out there, and you're traversing this thing which is completely wide-open and unenclosed, and yet the Forest of Steel which you were deeply embedded inside of, in a very three-dimensional way, knocked the light way down in there. And you found yourself going through things, yes, at a walking pace to be sure, and yet it still had some kind of amusement park ride ambiance to it anyway. There was all this stuff all around you. Very close at hand all around you. And farther away, too. Way the hell up above you. And below you. And across from you, over there partially visible through The Forest, the Payload Changeout Room sat and waited for you. Downtown.

And whether you yourself are resonating with any of this, you may rely on the fact that every single time I crossed this catwalk, I was feeling it.

I need to shut up about this thing. Somebody's going to come and scoop me up and take me away if I don't shut up about this kind of stuff.

"SQ PLF"

Square Platform.

And for this one, we get nothing.

Nothing at all.

Where this platform might have been, and what it might have been, and why it might have been singled out for special attention, are lost from my memory, but hopefully not forever (memory is a funny thing that way), and if at some point later on, something jogs this one back into my sensible consciousness, I'll return here and fill you in on it.

But for now... no.

Nothing.

"CATW 163"

Catwalk, elevation 163 feet.

And this is the catwalk to the OMBUU, and the OMBUU (Orbiter Mid-Body Umbilical Unit) is a whole little world unto itself.